Miles to Windward

MAKING THE 2,500-MILE PASSAGE FROM HAWAII TO RANGIROA

Story and photography by Linda Collison

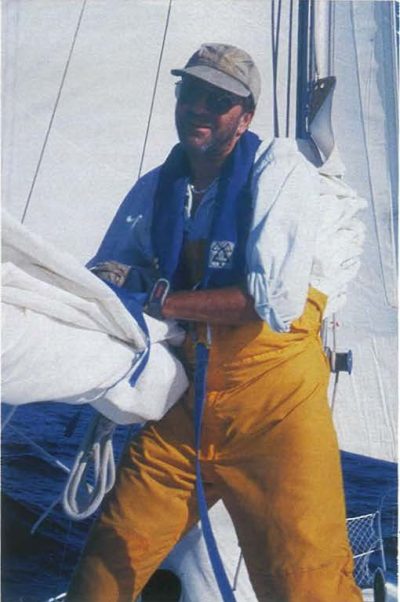

Bob, snugs down the main midway through the passage.

We had been motoring since Miloli’i, and I was at the helm watching the remains of a calm Kona Coast sunset. To the west Mauna Loa was hidden by a familiar band of clouds. But as we left the vol cano’s shadow it felt like somebody flipped a switch, as the wind shot up from 2 knots of light and variable to 25 knots of northeast trades. “Welcome to South Point,” I said to my hus band as he came up on deck to set sail. Hawaii’s South Point is known for its strong, gusty winds and rough waters. Bob, however, was looking a little queasy as he unfurled the jib. As queasy as I felt.

“Kill it,” he said, and the last diesel throb was swept away by the wind. Water surged against the hull, and I looked over my shoulder at the black hulk of land that is the southernmost point in the United States. A scattering of sodium lights glowed like cheery campfires, and I thought to myself that it would be at least anoth er 2,500 nautical miles before we saw land again. Still, in spite of the slight feeling of sea sickness, I had no qualms. After years of plan ning for our first South Pacific voyage, we were finally under way.

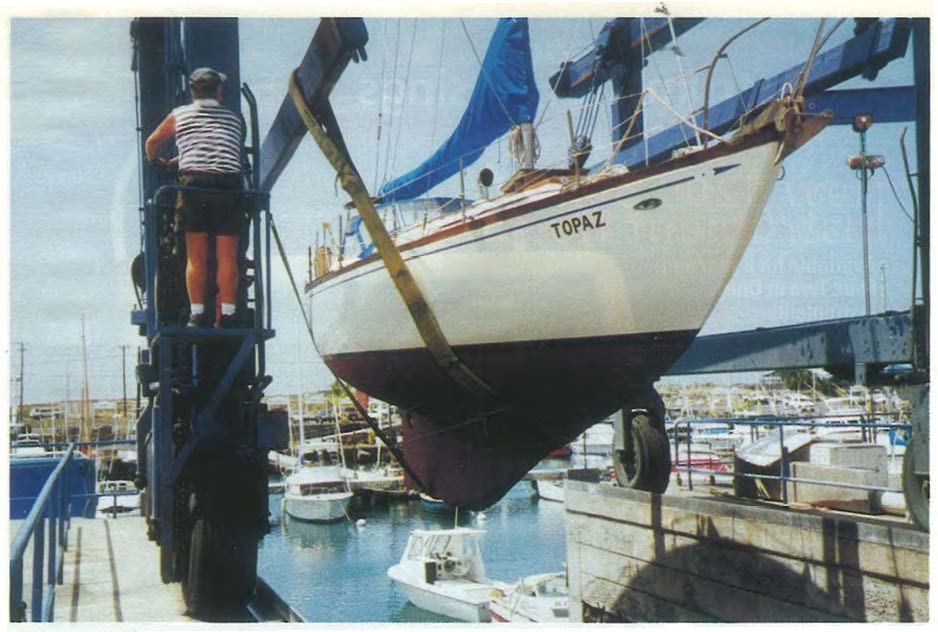

Our boat Topaz is a Luders 36 built by Cheoy Lee in 1972. We found her in 1993, shortly after moving from Colorado to Hawaii’s “Big Island.” Bob saw the notice tacked to the wall in a local fishing supply store in Hilo and was instantly struck deep by Cupid’s arrow.

“This is exactly what we’ve been looking for,” he said, starry eyed. And indeed, the old fiber glass sloop seemed to fit our bill. She was the right size for the two of us, she had a sound hull, and because she was in want of some upgrades and cosmetic repairs, she was affordable.

Dialing the phone number on the notice we arranged to meet the owner under a banyan tree on the shore of Reed.:.s Bay, Hilo’s no-frills anchorage, where Topaz was moored. Reed’s Bay is a typical waterfront where hoodlums and ne’er-do-wells mingle with honest fishermen

and yachties, and you can’t always tell them apart. We tried not to appear vulnerable as we scanned the beach looking for the owner, a dark haired, dark-bearded haole, or nonnative Hawaiian, in a flowered shirt.

“Is that him?” I said out of the comer of my mouth, nodding toward a rather scruffy looking character leaning against a tree. He looked like a cross between Charles Manson and Jimmy Buffett.

“I think so,” Bob said, subconsciously patting the wad of bills deep in his pocket. It felt like we were scoring a drug deal instead of buying a legitimate, registered sailboat.

We had found our man. And after a cursory inspection Topaz was ours. Had we been more cautious, we would have had her professionally surveyed. We should have at least taken her out and sailed her, but she appeared to be a sound boat, and we were smitten. Sometimes you just get lucky.

To make a bluewater passage had been Bob’s dream since he was a boy. He has fond memories of summers spent sailing a 16-foot sloop on Lake Michigan. As a girl I had also dreamed of exploring remote places, though not necessarily by boat. At the time we bought Topaz I had logged 11 days on the water, many of them more in the water than on it since I spent so much time righting a capsized Sunfish.

Eventually I learned to sail, and somewhere along the line Bob’s dreams infiltrnted mine as insidiously as his socks found their way into my drawer.

Eventually we found ourselves planning a major passage, just the two of us, aboard Topaz.

He laughed. “Are you kidding? You’ll never be ready.”

Bob and I scowled.

The Hawaiian Islands are among the most isolated in the world_ and sailing to anywhere else involves a significant bluewater crossing. Over the years we discussed alternatives, and eventually agreed to go south, mostly because it was warm. We decided against going southwest, even though it follows the prevailing winds, since we would miss too many interesting places. Ultimately we decided to beat into the trades and head first for the Tuamotu Islands, southeast of Hawaii, then sail south to Tahiti where we would pick up the “milk run” through the South Pacific.

Although basically sound when we bought her, Topaz needed a lot of work to ready her for the passage. And Bob and I needed experience sailing her. Over the next few years we cruised Hawaii’s coasts and made excursions across the channels to the neighboring islands of Lanai, Maui and Oahu. When we weren’t sailing we hauled Topaz out, put her in a cradle and rebuilt her bit by bit.

The years slipped away; Topaz was looking sharp and sailing well. One day a friend asked us when we were leaving on that big passage we always talked about.

“As soon as we’re ready.” He laughed. “Are you kidding? You’ll never be ready.” Bob and I scowled.

Our friend laughed again. “Come on, it’s a boat. There’s always something that needs fix ing, a retrofit for some piece of equipment you think you’ve got.to have.” “It’s not just the boat. Bob and I could bene fit from a few more seasons of inter-island sail ing,” I said. “I need more practice with celestial navigation and … ”

“Like I said, you’ll never be ready.” “So what do you suggest?”

“Easy. You pick a date, and you go.”

As cavalier as it sounds this was sound advice and we took it. Some might say we’re roughing it with no oven, no refrigerator, no freezer, no freshwater shower, no radar and only a wind vane for self-steering. But in the end you go with what you’ve got, or you don’t go at all.

The Tuamotu Archipelago, also known as “The Dangerous Archipelago,” is a group of 78 islands, most of them coral atolls, clustered around latitude 20 south between the Marquesas Islands and Tahiti. Rangiroa, at the northwest end, is the largest in the group and the second largest atoll in the world. Moruroa, at the opposite end, was France’s nuclear test site from 1966 to 1996. Today family-run boarding houses called pen sions, dive shops and black pearl farms have replaced the explosions.

We chose Rangiroa as our first landfall. This would require beating into the prevailing easter ly trades for the whole passage in order to make our 9 degrees of easting. Fortunately the trades stayed from the northeast most of the way so we didn’t have to tack for our destination. To me the waves seemed enormous, yet the sky was blue and the barometer stayed steady: no storms in the offing, just the powerful wind pushing the water into dazzling, silver mountains. I found it challenging to live on an angle for so many days, having to hold on to keep from being thrown about the cabin as Topaz trundled on mile after blue mile like a sturdy Conestoga wagon.

Because the decks were awash most of the time, water inevitably found its way into the cabin through portlight seals that had never before leaked. We managed to keep the elec tronics dry but our underway berth turned into a sponge. Both Bob and I developed itching, irri tating “salt sores” on our arms, thighs, trunks and groins. Spritzing with fresh water and slap ping on aloe vera gel gave us some relief.

As we approached the equator the bright days became brutal, especially during those cruel hours between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. We rigged bed sheets to the boom gallows to provide a sliver of shade for the helmsman, who occasionally received additional relief in the form of an odd wave reaching over the weather cloth.

“Here Bob; drink this. That’s an order.”

Although Bob got to be captain because he was more experienced, I elected myself chief medical officer and water police, which often meant reminding my husband to take a sip. Having worked for many years as a registered nurse I knew that even a mild case of dehydra tion can make you prone to headaches, fatigue and mal de mer. And there was no reason to make life any harder than it needed to be.

Topaz carries 100 gallons in two separate tanks, but I found we weren’t drinking our allotted ration, since although filtered and purified the water tasted like a fiberglass tank. Additives such as KoolAid, lemonade and Gatorade justmade it worse. The only thing that made the water palatable was fresh limes. Our supply lasted 16 days. I should have brought more.

We soon found the choice spot to rest was the lee-side cockpit seat-if you didn’t mind the occasional splash that came over the dodger. Belowdecks was too salty, hot and stuffy to sleep. And not much drier than topside.

In spite of our minor discomforts we couldn’t have asked for more perfect conditions. Topaz was sailing well; we were making good time; we were making our easting. This was sailing to weather, as good as it gets. This became most apparent every evening when we tuned the SSB to Ron DuBois’ Honolulu-based radio net.

“Foxy II, Foxy II, this is Topaz, over.”

“Topaz, this is Foxy II. How do you copy?”

Ron’s voice coming across loud and clear every evening was a reassuring sound. Having just listened to the broadcasts of other boats strung out all over the Pacific, boats whose crews were enduring cold weather, relentless gales, contrary winds, mechanical failures and other problems, we felt a little guilty. We’d sign on, give our position and have nothing to report except good progress, blue skies and fabulous sunsets. Life was good for us, if rugged.

Remarkably, we had only one significant problem, when our self-steering broke down near the end of the passage. Our old RVG wind vane was a tireless helmsman-we seldom took the wheel unless we were dodging squalls-but and mal de mer. And there was no reason to make life any harder than it needed to be.

Topaz carries 100 gallons in two separate tanks, but I found we weren’t drinking our allot ted ration, since although filtered and purified the water tasted like a fiberglass tank. Additives such as KoolAid, lemonade and Gatorade just made it worse. The only thing that made the water palatable was fresh limes. Our supply last ed 16 days. I should have brought more.

We soon found the choice spot to rest was the lee-side cockpit seat-if you didn’t mind the occasional splash that came over the dodger. Belowdecks was too salty, hot and stuffy to sleep. And not much drier than topside.

16 days out a piece of the trim tab linkage cracked at the spot of a previous repair. Jury-rig ging a fix couldn’t be done from the deck, so we elected to hand steer the last four days, lashing the wheel when wind and seas allowed.

Days became nights, became days, became nights with a rhythm as seamless as breathing.