Using Fact and Fiction to Create Verisimilitude in Historical Fiction

Last week I was participating in a thread on Historical Novel Society’s Facebook page, where an author had started a topic asking if it was a historical or literary crime to manipulate the date of an actual event in their story.

I’ve been thinking this question all week, remembering the advice I’ve received over the decades about the craft of fiction writing and applying it to historical fiction. Realistic historical fiction (as opposed to historical fantasy) is a genre that is particularly difficult because the writer is challenged to recreate a setting that must conform to the accepted model for it. Yet literary historical fiction (which is what I read) should be more than history-lite. I want more than History-101 spiced up with imagined sex scenes.

Fiction is an art form in which we experience life from another point of view. It engages and transforms both the writer and the reader. Yet how to do it? What follows is a pastiche of advice. When I have followed this advice I’ve produced some of my best writing and when I’ve ignored it, some of my worst.

Before I begin ranting against obsessing on “historical accuracy” when writing historical fiction, let me say that before I wrote my first (published) historical novel (I have written many practice novels that have never seen the light of day) I researched the 18th century from a European perspective for four years and I continue to research the period. I spent time aboard four historical ships. I enrolled in college level history classes (and am currently enrolled in history classes, working toward a second degree.) The passion continues, research has become a hobby. But for me research is not the endgame.

As a writer what I want to achieve is not historical accuracy so much as the “V” word. Verisimilitude. Too much emphasis on accuracy can suffocate the story leaving the characters dead on the page. The point of an historical novel, or any novel in my opinion, is not to prove what a clever fellow the author is. That being said, the historical novelist must know what it is she is writing about, as if she had lived it herself. This is where the art of writing comes in and if it were easy everyone would write and publish a novel.

How to create verismilitude? Hard to say, yet we know it when we read it. Here’s an example that we all can relate to. The stories of old people.

How to create verismilitude? Hard to say, yet we know it when we read it. Here’s an example that we all can relate to. The stories of old people.

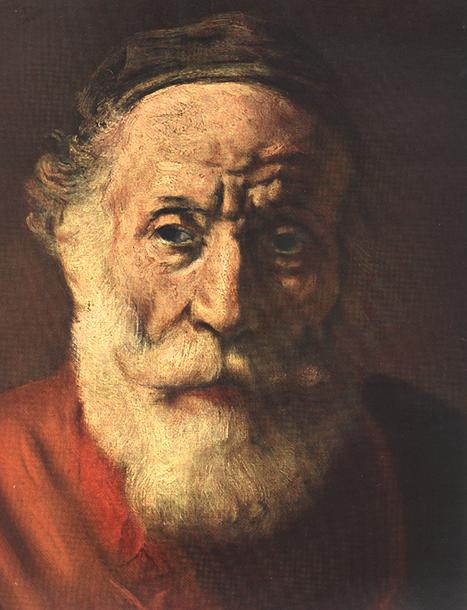

My grandfather was a great storyteller; partly because he knew how to tell a short but interesting story and partly because he led an interesting life in interesting times. Born in 1900, at a time when automobiles were still rare, penicillin had not been invented and televisions and computers were the stuff of science fiction, John W. Leonard (not pictured, that be Rembrandt’s Old Man) was a youngster when the Wright Brothers made the first airplane flight at Kitty Hawk, he recalled meeting the aviator Charles Lindbergh after he made the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean and he watched with millions of others around the world as Neil Armstrong took those first giant steps for mankind on the moon in 1969. “Bill” Leonard, whom we grandkids called Bebop, lived to hear about his granddaughter jumping out of perfectly good airplanes. He lived through the Great Depression, two World Wars, was married to one woman for more than fifty years and raised six kids. Bebop could play the piano by ear, he loved a good song, a good joke, a good road trip, and he knew how to tell a story and keep your interest. I always believed my grandfather’s stories because I knew he had lived them. His stories rang true, they were from the heart, they were from experience. My grandfather, like your grandfather, created verisimilitude.

Yet I’m sure more than once Bebop got a date wrong, had the sequence of events out of order, or confabulated something along the way. Does that make his stories less real? They were his truth and captured his essence and the life he lived far more than the most assiduous biographer could ever do.

Historical fiction writers probably all wonder how accurate we should be. This is an angst that never really goes away but my resolution is to be accurate without deforming the story arc and overburdening the characters themselves with chronology. In character-driven fiction story comes from character and setting. As the writer I must know that setting intimately, I must live it. When I write it I might confabulate some details and ignore others, just like Bebop did when he told us his stories. That is my goal.

One example of my own angst over facts from my own historical fiction is HMS Richmond, a “real” frigate that took part in the “real” battle of Havana in 1762. What I have concentrated on is capturing what it was like to have been aboard a frigate of the British Navy during this time period. My Richmond has a life after the battle of Havana that is probably different than the “real” Richmond had. Parallel lives, if you will. But I strive to make my story believable, not by piling on information to “prove” I have done my research or inserting too much back story. Whatever isn’t necessary to the evolution of my characters or creating the mood or setting must go. If I know my setting, if I have been living in the 18th century this familiarity will seep through the page. It’s the “telling detail” not reams of description or fact-dropping that lend authenticity to the paragraph.

If you find you are more enthused about writing the facts than the character’s response to living in that long ago world, then perhaps the book you really need to write is nonfiction. When I read I don’t want to be taken out of the story for a history lesson, I want to be transported back to the time and feel immersed in it. I want to vicariously live that history. Writing historical fiction is difficult because it involves time travel and astral projection, or at the very least, channeling past lives. I am only partly jesting when I say that. An author must do whatever she can to get to the heart of the story and find the truth in the historical setting.

In writing a realistic historical novel I am not defending a thesis. On the other hand, writing memorable fiction is more than just making up stuff that might have happened. Fiction tells the truth the facts cannot.