Bob and I had the pleasure of meeting author Sam Low and his kinsman, navigator Nainoa Thomson at Imiloa Astronomy Center in Hilo, Hawaii, last June at a book talk and signing of Hawaiki Rising. The book release coincided with the beginning of a new voyage for Hokule’a, Hawaii’s traditional voyaging canoe, on the fortieth anniversary of its creation.

Bob and I had the pleasure of meeting author Sam Low and his kinsman, navigator Nainoa Thomson at Imiloa Astronomy Center in Hilo, Hawaii, last June at a book talk and signing of Hawaiki Rising. The book release coincided with the beginning of a new voyage for Hokule’a, Hawaii’s traditional voyaging canoe, on the fortieth anniversary of its creation.

I’ve been interested in the history and renaissance of Polynesian voyaging canoes for many years. Having sailed from Hawaii to Polynesia and back in a fiberglass sloop with Bob, just the two of us (with all the modern gadgets such as GPS ) we developed an even greater appreciation for the Polynesian voyagers and their traditional methods of wayfinding.

In our large collection of books we have just about every book related to Polynesian nautical history that is in print today. When I heard about the release of Hawaiki Rising, I knew I had to read it. But I wondered if it would be a derivative of the handful of books that were already out there. Another crew-member telling his story, that sort of thing. Much more than a derivative, Sam breaks new ground in discussing the social and cultural problems the crew faced.

In Hawaiki Rising, Low adds to and enriches the growing library of Polynesian voyaging. An anthropologist, Sam’s roots are deep in Hawaiian soil; he is a direct descendent of John Palmer Parker and a cousin of Nainoa Thompson, and has sailed three times on the Hokulea. He has also worked as an underwater archaeologist and a filmmaker – all fascinating occupations – and his academic credentials are impressive. But for me, Sam’s greatest talent is as a writer. He has a unique perspective on the Hokulea story, sharing the tension and turmoil on board, and he has the skills to craft a compelling history.

I wrote a review of Hawaiki Rising and reached out to the author via his website. Although a very thorough interview is posted on his website, Sam graciously agreed to answer my questions. So here we go…

I would like to ask you a little more about your Hawaiian roots and connections. You said your father was raised in Kohala? Can you tell me more about your father, your Ohana, and your Hawaiian roots?

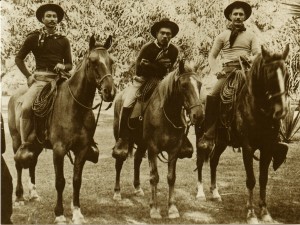

My great grandfather, John Somes Low, traveled from Gloucester, Massachusetts to the Big Island in 1850, to seek his fortune. In 1857 he married Martha Kekapa Namoomoo Parker Fuller, the daughter of Mary Parker and grand daughter of John Palmer Parker, head of the Parker Ranch, the most affluent of the haole settlers in Waimea. His son, Eben Parker Low, my grandfather, was born and raised on the ranch and became a famous cowboy. They called him Rawhide Ben. Ben later founded his own ranch, Puuwaawaa, on the big island. In addition to his exploits as a roper of wild cattle on the slopes of Mauna Kea, he was famous in the islands for sending three cowboys to compete in the Cheyenne Roundup in Wyoming in 1908. They entered the roping contest and placed first, third and fifth – a blow for the haole cowboys who doubted they could rope at all.

My father was sent away [from Hawaii] to school in Connecticut when he was 17 years old. The story goes that his father went bankrupt at home and he had no money to pay for his son’s return – so my father decided to make his way in New England. He grew up to become an artist, teacher and director of an art museum in New Britain, Connecticut, married a beautiful and talented New Englander, had me, and stayed on.

I knew that my father was different from other dads at an early age. For one thing, he did not work in an office, he went to his studio to paint, or to Loomis School to teach art, or to the New Britain Museum of American Art where he was the director. My mother was an artist, too, so I grew up in a very creative family. And my father was the only dad that I knew who played the guitar and sang songs in Hawaiian. The fact that I was part Hawaiian didn’t really have much meaning for me, growing up in a very haole world in New England. What fascinated me most were stories my father told about HIS father – a famous cowboy from the Big Island known as “Rawhide Ben Low.” How could I not be interested in a grandfather who was a cowboy? I loved dad’s stories of Rawhide Ben growing up on the Parker Ranch, hunting wild cattle on the slopes of Mauna Kea, losing his arm in a roping accident, and founding Puuwaawaa Ranch. Still, I really did not know what “being Hawaiian” meant.

In 1964, after graduating from Yale University, I was commissioned as a Naval Officer and ordered to a ship in Pearl Harbor – which was my choice – I wanted to see Hawaii.

My plan was to drive a battered Volkswagen across country to San Francisco, ship the car to Hawaii and fly to join my ship. On the day that I left home, my father took me aside.

“I will see you in Hawaii,” he told me. “I have not returned but now is the time. You will be there and I want to see my family.”

He died in his sleep that night of a massive heart attack.

Later, in Hawaii, an elderly cousin took me aside. “When your father never came back, some of us in the family were angry with him. We felt that we were not good enough for him. But there is another reason. When he left the islands, he went to a kahuna for a blessing. The kahuna told him that he would die young and that he would never come home. I think he did not come back because he was afraid to. And now the kahuna’s story has come true. But I am glad that you are here. In you, he has come home.”

It was not until I arrived in Hawaii for the first time in the fall of 1964, as a young naval officer stationed on a ship home ported in Pearl Harbor, that I began to get an inkling of my Hawaiian identity.

I lived on Sunset Beach for about six months in a house I rented from the famous surfer Fred Van Dyke. During that time, I got to know my aunt, Clorinda Lucas – and I was introduced to an old-time, authentic Hawaiian life style by staying with her in Niu Valley. Clorinda was a well-known social worker who dedicated her life to helping Hawaiians. Almost every day, Hawaiian families would visit her home in Niu and be welcomed to discuss their lives, their joys and sorrows, with Clorinda. And, when needed, Clorinda would find a way to help them. It was this “helping” ethic that I found most fascinating and that introduced me to, if you will, the “aloha spirit.”

At that time, I did not really see much left of an authentic Hawaiian culture. None of my family spoke Hawaiian – with the exception of Clorinda who knew a few sentences and phrases. All of them, like so many Hawaiians, had been raised to deal with a haole world. I did not see any classic hula. The culture seemed to be dying.

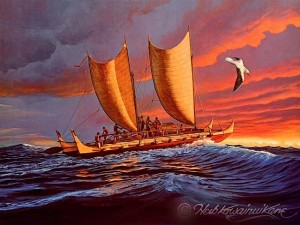

In 1976, I read about Hōkūle‘a and her successful voyage from Hawai‘i to Tahiti – carrying her crew 2400 miles in thirty-five days. Even more astonishing, she was navigated by Mau Piailug, a man from a tiny Micronesian Island who found his way as his ancestors always had, without charts or instruments, relying instead on a world of natural signs. I determined to make a film about this story, The Navigators – Pathfinders of the Pacific which has just been re-released in high definition video, and to tell it from the perspective of the scientists who had discovered the truth about ancient Polynesian explorers and men like Mau Piailug who continued to sail in the old way.

I spent two years traveling the Pacific with experienced archaeologists as guides, retracing steps taken by early Polynesian mariners. I sailed with Mau Piailug from his home island of Satawal. He told me how he navigated by the stars and by signs in the wind and waves using secret knowledge handed down from father to son over thousands of years. I spent time in Hawai‘i with Nainoa Thompson who combined Mau’s teachings with his own discoveries to reveal how ancient Polynesians may have guided their canoes. I began to feel a stirring in my blood. I am one-quarter Hawaiian, and three-quarters haole—descended from a Hawaiian aliʻi (a chief) and a New Englander who ventured to the islands in 1850 seeking wealth and bringing with him disease and an alien way of life. At first glance, this influx of outsiders seemed to have destroyed Hawaiian culture. But as I visited the islands more often, I discovered an astonishing revival of the Hawaiian language, poetry, dance and all the other arts of indigenous life. Hawaiian culture had not died. It had gone underground—waiting for a spark to ignite it. That spark was Hōkūle‘a.

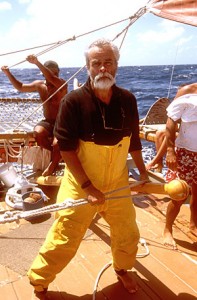

In 1995, I was at the departure ceremonies for Hokule’a when she left on Na ‘Ohana Holo Moana – a voyage to join up with 6 other canoes and sail from Tahiti back to Hawaii via the Marquesas. Nainoa came up to me and said, “Do you want to sail back with us on an escort boat from Tahiti, one of the crew couldn’t make it and I think I can get you a berth.” It was an unexpected honor. Naturally, I said yes.

In April, I flew to Nuku Hiva and joined the crew of Rizaldar, a 43-foot Swann cruising-racing boat, captain Randy Wichman. On April 23rd we set off from Nuku Hiva for Hawaii in the company of 6 canoes.

The trip aboard Rizaldar was exhilarating. And on that voyage, I found a new meaning and mission. After we had set foot on Hawaiian soil, I wrote: “Reflecting back on the trip, I remember one night in particular. As we moved through the Equatorial Counter Current, during the midnight to six watch, I experienced the arc of stars above me wheel across the sky. Some tribal people believe the stars are the spirits of their ancestors. On that night, I imagined that a pair of stars rising off the starboard bow were the spirits of my mother and father. I felt a deep welling of emotion. I imagined the Milky Way to be a trail of my ancestors stretching back to the original seeding of my bloodline. As I looked over the side of the vessel, I saw glowing plankton turn the sea as effervescent as champagne. Large globs of green light flared up, shimmered for an instant, then slowly faded. I seemed to float through a universe of jewels, the stars above and the sea below. Here, perhaps as far away from the influence of modern life as one can get, time stood still. I imagined myself on the deck of a Polynesian canoe, making the first voyage to Hawaii. The past lived.”

I kept a log of the voyage with the idea of writing an article, which was published by Sail Magazine and is available at: http://www.samlow.com/sail-nav/starpaths.html.

In that article, I wrote: “My mission here is personal – a voyage back to my own roots. My father was Polynesian — born in Hawaii but sent as a teenager to a boarding school in Connecticut. He stayed in New England, and died there, never having returned to the islands. I am returning for him. “

In 1999, I was invited by Nainoa to voyage aboard Hokule’a from Tahiti to Rapa Nui (Easter Island). My job would be to document the voyage.

In my log, on October 21st, after making landfall, I wrote: “On this, my last day on the island, I sit on a ledge of rocks down by the harbor in Hanga Roa, lost in a reverie. As I listen to the waves crash on the reef offshore, I remember the excitement of sighting Rapa Nui and the inner peace of the evening before our arrival, as Höküle’a ghosted along the coast. We had all lingered on deck, enjoying the last few moments of comradeship with each other and our canoe. Hotu Matua (The Polynesian navigator who discovered Rapa Nui) and his men must have seen what we were seeing – the dark smudge of the island against a backdrop of stars – and they must have heard what we were hearing: the rush of wind over sails, the soft lap of waves on twin hulls, the murmur of sailors as they sit shoulder to shoulder, waiting for the first scent of land to reach them.”

In 2000 I served aboard the canoe on a voyage from Tahiti to Hawaii and in 2007 I sailed from Chuuk (in Micronesia) to Mau Piaulug’s home island of Satawal for the pwo ceremony – an initiation of Hawaiian and Micronesian navigators as masters of the art.

You’ve been a part of some incredible voyages, as listed on your webpage. Can you tell me about your early interest and connections with sailing and voyage making? Something about your experience in the Naval Reserves, if applicable?

From compendium

“This is a story of the sea – and it is natural that I should choose this as my first book because I have been attracted to the sea all my life. I grew up on a small island – Martha’s Vineyard – and I spent most of my time on or in the ocean. When I graduated from college I joined the United States Navy as an officer and served aboard a ship on Yankee Station off the coast of Viet Nam at the beginning of the Viet Nam war. Afterwards, I studied nautical archeology and was a member of a team of National Geographic archeologists excavating a Roman shipwreck off Italy, a Byzantine shipwreck off the coast of Turkey and a Roman seaport a few hundred miles north of Rome. I have always owned boats, both sailing and power, and have written about them and to this day I spend a great deal of time on the ocean.”

As you know, I’m a big fan of Hawaiki Rising. You have dared to bring out the tensions between the Hawaiians and the Haloes involved in the project, presenting them with understanding. What is your relationship now, with the current Polynesian navigators?

It was important to tell the story of the Pilikia (Hawaiian word for “trouble”) during the early years of Hokule’a – the friction between Hawaiian and haole crewmembers – because it illustrated the anger that came to the surface when Hawaiians began to realize what had happened to their ancestors. The story of the conquest of Hawaii by outsiders, of the suppression of the Hawaiian culture, was not well known in Hawaii at the time. That story had been swept under the rug. It was only natural that, once Hawaiians learned about it that they would become disillusioned and angry with how all this had been kept from them – was not taught in schools or spoken of by their parents. I needed to write of the anger because I needed to tell that story of oppression so my readers would understand the importance of the revival of Hawaiian culture which was brought about by voyaging.

You ask about my relationship with the navigators.

Nainoa Thompson, the chief navigator and mentor of all the others, is my cousin. When I go to Hawaii, I spend time with his mother and live in a guest house not far from Nainoa’s home where he lives with his wife and two children. Our relationship is close. We have sailed together and I have spent about six years interviewing him for the book. The process of reliving his past, he has told me, has helped develop his own thinking about navigation and wayfinding. I would say that the exchange, the working together, has created a bond between us.

Bruce Blankenfeld, another of the experienced navigators, is married to Nainoa’s sister and also lives next door. He took me under his wing early in the project and helped me understand the basic concepts of navigation. He told me stories that were essential to my understanding of the deeper basis of wayfinding and taught me a great deal about Hawaiian culture. He is a mentor and a good friend.

Chad Kalepa Baybayan, another of the experienced wayfinders, is a strong supporter of my work. We voyaged together from Mangareva to Rapa Nui in 1999 and got to know one another. I interviewed him extensively for the book and we also traveled together to Satawal, aboard Hokule’a, for the pwo ceremony in which Mau bestowed highest honors on the Hawaiian navigators. I consider him a friend as well.

I want to know more about your filmmaking projects. How did you become a producer/director? Are your films available to the general public?

At Harvard, I studied anthropology and what is known as ethnographic filmmaking – a deep kind of documentary in which the filmmaker, often an anthropologist, lives with the people for sometimes years at a time and documents the deep aspects of their lives. Two of the best ethnographic filmmakers had Harvard connections, Tim Asch and John Marshall, and they both took me under their wing and taught me the basics of filmmaking. John loaned me an Auricon camera, gave me some film, and helped me when I went off on a Gloucester Trawler to the Grand Banks to make my first film (it never progressed beyond the first assembly but was a seminal experience).

In 1978, I got a job as senor researcher on a remarkable Public Television series called Odyssey. The executive producer of Odyssey, Michael Ambrosino, was the creator of the first hour-long documentary series for PBS, called NOVA. He was another mentor. In my first year at Odyssey, I became what is called an acquisitions producer. Odyssey produced 12 programs a year, 6 of which were purchased from other sources such as the BBC and Granada Television in the UK and “remade” for American Public Television. The English programs were often about 6 to 10 minutes too short for American TV and so I traveled to the UK where I went through the outtakes with a skilled editor and added new sequences to the films. By so doing, I had to deconstruct the basic structure of each film, understand how the story was told, find places where new scenes could be inserted without disturbing the basic rhythm of the film. I had to understand the film. That was a crash course in filmmaking, better I think than any film school. I “remade” four films in the first year.

In the second year, I proposed a film of my own – The Ancient Mariners – about how underwater archeologists, working in the Mediterranean, had excavated three ships – Greek, Byzantine and Arab – that demonstrated a fundamental change in shipbuilding technology that made possible the building of the large vessels used by Europeans to discover and explore the world’s oceans. That was my first real film. It was my graduation exercise.

Three years later, Odyssey having competed its run, I produced The Navigators – Pathfinders of the Pacific, which tells the story of my ancestors’ settlement of the Pacific. That film cemented my interest in Polynesian voyaging and led, eventually, to the publication of Hawaiki Rising thirty years later. The Navigators has been restored and was re-released in January of this year and is now available on DVD for home viewing. It has been shown on the BBC and television venues around the world and has continued to be used in classrooms and is, according to many teachers I have spoken with, still the best movie available about Polynesian settlement and voyaging. It features unique footage we took of Mau Piailug during a two-week stay in 1982 on his island, Satawal, in the Caroline islands. It can be purchased from me directly on my website for $20.00 and will soon be available, I hope, on Amazon.com along with Hawaiki Rising. I think that the book and film work well together and am pleased that they are both now being used in classrooms and seen in homes all over.

As an anthropologist as well as a participant in the voyages of Hokule’a, where do you see traditional wayfinding and Polynesian voyaging going?

For the first 25 years of its existence, Hokule’a voyaged in the wake of our ancestors on a primary mission of recovering the skills and the pride of all Polynesians. Our people, whether in Tahiti, New Zealand or Hawaii had been suppressed by colonial powers – as have indigenous people all over the world. Hokule’a and her voyages are deeply symbolic to us all – and she has restored our pride of ancestry. In Hawaii, a profound revival of culture has occurred, to the point that the language, once ebbing away, is now being spoken fluently by an ever-increasing number of Hawaiians. In 1995, in fact, the fist cohort of Hawaiian students graduated from high school having spoken Hawaiian exclusively in their classrooms. Classic hula is back, replacing the ersatz versions common in Hollywood movies and Waikiki bars. Curing practices, aspects of our region and spirituality, chants, poetry, the martial arts and sculpture are all being revived. And voyaging is now strong throughout Polynesia, with traditional canoes sailing out of ports in Aotearoa (New Zealand), Tahiti, Tonga, the Marquesas and other islands – about twenty in all. So Hokule’a has pretty much accomplished her mission of restoring pride. She now joins with others on a different mission – supporting the effort of people around the world to seek a sustainable relationship with planet Earth.

As Nainoa once told me: “When you voyage, you become much more attuned to nature. You begin to see the canoe as nothing more than a tiny island surrounded by the sea. We have everything aboard the canoe that we need to survive as long as we marshal those resources well. We have learned to do that. Now we have to look at our islands, and eventually the planet, in the same way. We need to learn to be good stewards.”

This is not really a new mission. It is founded on basic Polynesian values. Ancient Polynesians fashioned canoes like Hokule’a with stone tools. They used koa wood for the hulls, breadfruit sap and coconut husks for caulking, and coconut fiber rope for lashings. With materials from the land they fashioned a vessel to blend with the sea.

“When our ancestors went to the mountains to cut down trees they did not think they were taking the tree’s life,” navigator Bruce Blankenfeld once told me. “They were just altering its essence, taking it from the forest and putting it into the sea, and in Hawaii the sea and the land are tied together. Everything in the sea has a counterpart on the land because on an island the land and the sea rely on each other for life.”

Polynesian islanders recognized the inherent “oneness” of their natural world because islands are fragile places where the interaction of man and nature is clearly seen. When they cut the trees in their valleys they must have noticed the effect of pollution from runoff on their reefs. This may explain why ancient Polynesians constantly balanced the resources of land and sea in their rituals. Some anthropologists call it “dualism” and believe they have discovered in such ‘primitive’ societies a yin and yang universal in human thought. But I think it’s simpler than that. If ritual reinforces ways of living essential for survival then it is no mystery why Polynesian islanders recognized the aholehole fish as ritually equivalent to a species of taro plant. Today, we are so distanced from this basic understanding of connectedness that we use a relatively new word to express it – ecology.

“When we sail we find ourselves surrounded by an empty ocean which forces us to turn inward and consider how to take care of ourselves, each other, our canoe,” says Nainoa. “Learning to survive on long voyages also forces us to consider how to survive on the islands we live on, it’s a microcosm for learning to survive everywhere. In Hawaii we are surrounded by the world’s largest ocean, but Earth itself is also a kind of island, surrounded by an ocean of space. In the end, every single one of us – no matter what our ethnic background or nationality – is native to this planet. As the native community of Earth we should all aspire to live in pono – in balance – between all people, all living things and the resources of our planet.”

To support this mission of pono, of balance, Hokule’a will sail around the world beginning in May, 2014.

As Nainoa tells us: “In our Hawaiian language we have a word—mālama—which means “to care for,” and I think it evolved from our own heritage of long distance voyaging. Our ancestors learned that to arrive safely at their destination they must malama each other and their canoe.”

“The wisdom and values of our ancestors enabled them to mālama Hawai‘i

and her surrounding oceans for nearly 2,000 years. By carefully managing their

natural resources, they were able to sustain a large, healthy population. Now, we

must learn to treat our planet in the same way.”

“In May. 2014, we will begin a voyage around the world to mālama honua

—“care for the Earth.” We will sail for approximately 36 months; travel more

than 45,000 nautical miles; and visit at least 26 countries, with 62 stops. During

the voyage, we will connect with communities that share our values and vision.

Returning home, we will bring with us lessons of hope and action as we navigate toward a safe, peaceful, and sustainable future for our children.”

(Follow Hokule’a’s Worldwide Voyage)

What’s next for Sam Low? What are you working on that you can tell me about?

For the next three years, while Hokule’a is voyaging round the world, I will continue to work to support her mission. I hope to give talks in the American hinterlands and up and down both coasts, where many people still think that Polynesia was settled by people who drifted on rafts (Kon Tiki did sell 50 million copies so I have a lot of work to do.)

I have been invited to write a chapter for a new book about Polynesian prehistory and will also take up a project I put aside long ago – a book about my grandfather, “Rawhide” Ben Low, a famous Hawaiian cowboy. Ben wrote a memoir which was never published and it is my kuleana – my privilege and responsibility – to finish it. He lived at a very interesting time, when Hawaiian culture was being both actively and passively suppressed, and I hope to weave a little of that theme into this new book so it will, in a sense, be a continuation of what I wrote about in Hawaiki Rising.

Writing that book will also be a continuation of my own personal search to discover what it means to me to be Hawaiian. I look forward to it.

***

Mahalo, Sam. I’m looking forward to reading that next book!

Visit Sam Low’s website